What is the ‘Missing Middle’ and why is it so important?

Sydney housing choices are currently polarised between the detached suburban house on a remote greenfields lot and the high rise apartment within a metropolitan centre. This is particularly true of new housing supply. The row housing of late 1800s / early 1900s and the latter art deco and 60s / 70s ‘walk-ups’ that fulfilled medium density low rise options with opportunities for gardens at grade are substantially missing from current housing choice and appropriately described as the ‘Missing Middle’.

The term is gaining momentum internationally and is better understood in the main cities of Canada and California that have initiated policies to diversify housing supply. These cities, like Sydney share similar prevalence in suburban character, and rate highly on global liveability indexes, and as demand for housing surges so do issues of affordability and greater housing diversity.

Here in NSW the term ‘Missing Middle’ has garnered broader application since about 2016 with the introduction of the ‘Low Rise Housing Diversity Code’ (formerly the ‘The Low Rise Medium Density Housing Code’) which was ‘committed to promoting more ‘missing middle’ development, such as low-rise dual occupancies, manor houses and terraces’.

The Low Rise Housing Diversity Code

The Low Rise Housing Diversity Code was designed to ‘promote housing choice and diversity’, facilitating affordability through ‘Increased housing supply’ and housing types that ‘provide private open space, in most cases at ground level, which allows families to socialise, play, garden and exercise in their own home’. An admirable aim which sought to address the ‘Missing Middle’ in terms of both housing type (low and mostly attached housing types with gardens) as well as affordability.

The Code regrettably failed (refer my previous blog post ‘Why the ‘Housing Diversity Code’ failed to deliver housing diversity’), primarily for political reasons. It represents a significant technical failure on the part of NSW Planning in implementing a policy which was perceived to have (but could not achieve) broad application across large strands of LGAs designated as ‘General’ and ‘Medium Density’ residential zones (most notably R2 and R3 zones). The perceived broad application of the Code was bound to get the NIMBY’s off side and it did.

In the context of cities like Sydney (much like other capital cities of Australia) the ‘middle’ in ‘Missing Middle’ carries greater relevance in that it is most pertinent to the ‘middle’ ring suburbs. These suburbs share greater access to the city, are generally well serviced by public transport, rich with both public and private amenity (parks, shops, health services etc.), and accordingly highly sought after. However, the predominant housing type is the detached house which has the associated land cost directly embedded into the purchase cost and accordingly is becoming increasingly unaffordable.

These suburbs are typically rich in character, with tree lined streets, and individual residences that date from the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Some of these suburbs (like Ashfield in Sydney’s west) are peppered with the 1960s and 1970s ‘walk-ups’ (described above), many nestled within pre-established tree lined streets.

To understand the significance of the ‘middle ring’ suburbs for ‘Missing Middle’ development we need to understand how these suburbs evolved within Sydney’s metropolitan history.

Fig 1. Typical 1960s three storey walk-ups in Ashfield (source: Google Street View)

Sydney’s evolution

The original city of Sydney at Circular Quay was a mixed use urban centre (the original town) that could be traversed on foot before the advent of modern transportation. It has since moved towards becoming a CBD (Central Business District) servicing the metropolitan area although it is now transitioning back towards a more mixed-use / residential, albeit high density centre.

The first major expansion of the metropolitan area in the late 1800s was facilitated by rail. Heavy rail in particular facilitated the creation of new suburbs centred around new railway stations, to the north-west, west, and south-west of Sydney. These railway stations facilitated new centres (such as Ashfield, Burwood, Campsie, Chatswood etc.) where the surrounding public infrastructure; street layout, parks and other public amenities were again laid out on the basis of walking populations. The transportation nodes facilitated Main Streets and town centres (providing opportunities for retail shops and other private amenities). These middle ring suburbs are generally well laid out and are relatively well connected for greater walkability, with urban block sizes that can be traversed on foot (although not without flaw).

They were subdivided in the early 1900s primarily on the basis of free standing dwellings, corresponding with the aspirations of Ebenezer Howard’s ‘Garden City’ and other similar movements post federation which prioritised the free standing house on a freehold lot as the predominant housing model.

A further expansion occurred with the increased popularity and affordability of the motor car. This second metropolitan expansion came without an inherent need for walkability, given that the primary mode of transport was the motor car. Accordingly many of these suburbs in the outer periphery of the metropolitan area are not so well suited to densification without rail (where it is mostly absent), and not without difficult consolidations or reclamations to insert new streets, parks and other characteristics suitable to greater walkability and density.

It is the first zone of Sydney’s expansion, the middle ring suburbs, that are better suited to moderate densification, because the public infrastructure (streets and parks) were already laid out on the basis of walkability and accordingly can more readily sustain greater density.

Sydney Now

More recently, Governments (both state and local) have taken an expeditious approach to housing supply. It has been substantially two streamed:

To facilitate expansion of Sydney into greenfields areas where free standing houses (and the supporting infrastructure) can be built unencumbered by preexisting development, and;

By concentrating and facilitating high rise development around metropolitan railway stations and their associated town centres as high rise apartment development without having to intervene into the surrounding suburb they service.

While both of these approaches have value in increasing Sydney’s housing supply, the unwritten subtext of this approach is that:

It circumvents the (NIMBY) protectionist policies of established communities, and;

It also plays into the hands of large development companies that undertake such projects (and actively lobby for them via organisations such as the Urban Taskforce).

It’s interesting to note that the Urban Taskforce were very vocal against the ‘Low Rise Housing Diversity Code’ and partnered with suburban action groups to lobby against it, as its application would redirect part of their constituents’ ‘market share’ of supply towards better suited smaller development players.

The other issue with both of these streams of development is that they are relatively unsustainable. The former encroaches further into pastureland and forests while increasing dependance on the motor vehicles and great infrastructure per dwelling at the remote periphery of the metropolitan area. The latter is dependant on energy intensive building types, notably towers that are demanding on resources for construction, ongoing servicing and disruptive to their neighbourhoods in terms of concentration, scale, streetscape, and associated adverse environmental effects.

Independently of their external environmental consequences the two streamed approach limits housing diversity and the residential amenity that can be afforded by a greater diversity of housing types and locations.

Addressing the Missing Middle

The Missing Middle plays an important role in that new housing types can be inserted into established well serviced neighbourhoods, providing greater diversity in locations well sought after, at a lower price point to other predominantly available housing stock.

But in order to better address the ‘Missing Middle’ and the failures of the ‘Low Rise Housing diversity Code’, there are several factors that are critically important:

To provide a strategic approach to increasing density that does not extinguish or overwrite the character of existing suburbs (that would attract the wrath of NIMBY politics which could serve to diminish policy effectiveness).

To recognise the particular layouts, subdivision arrangements and lot sizes of middle ring Sydney in framing a policy to achieve greater density.

To more specifically Identify strategies and project types that can deliver necessary uplift in housing supply coupled with improvements to the public domain (while concurrently minimising any impact on existing neighbours).

Understanding that redevelopment requires upwards of 4-5 dwellings to replace a detached (single lot) residence to achieve economic viability.

The above could be developed towards a more ‘surgical’ approach to delivering strategic ‘Missing Middle’ projects that amplify housing diversity rather than broad, tenuous policies that can be diluted through escalating levels of intervention by local Councils in response to broad NIMBY activism.

So is there a Solution?

I was fortunate to be given an opportunity to participate in such an approach. I was part of a collaborative team of Architects (notably Hill Thalis, McGregor Westlake and Bennett and Trimble) with the assistance of JMD Landscape Architects, and a team of land economists and quantity surveyors to explore alternatives to density at different scales that address the problems with new housing developments (dense high rise metropolitan centres and new residential land release areas). A third project category sought to explore opportunities towards increasing housing supply within the ‘middle ring’ suburbs of Sydney without substantially altering their character. This work was undertaken for the NSW Government Architect to assist in advising both developers and policy makers of alternatives to ‘Business as Usual’.

The team I was invited to participate with, Hill Thalis, explored the high density context, Bennett and Trimble explored the possibilities of the low density greenfields context while McGregor Westlake explored the possibilities for the ‘Missing Middle’ using the Sydney suburb of Ashfield and its surrounding context as a suitable ‘middle ring’ case study.

Collectively we shared similar methodologies and metrics (surrounding walkability, access to parks, access to transportation and other key parameters) to tailor defensible frameworks for each proposal. In all 3 case studies the proposals demonstrated improvement in key performance metrics supported by economic input to demonstrate that public amenity and housing supply can be improved with at least economic parity with ‘Business as Usual’, but different approaches were required to secure good outcomes.

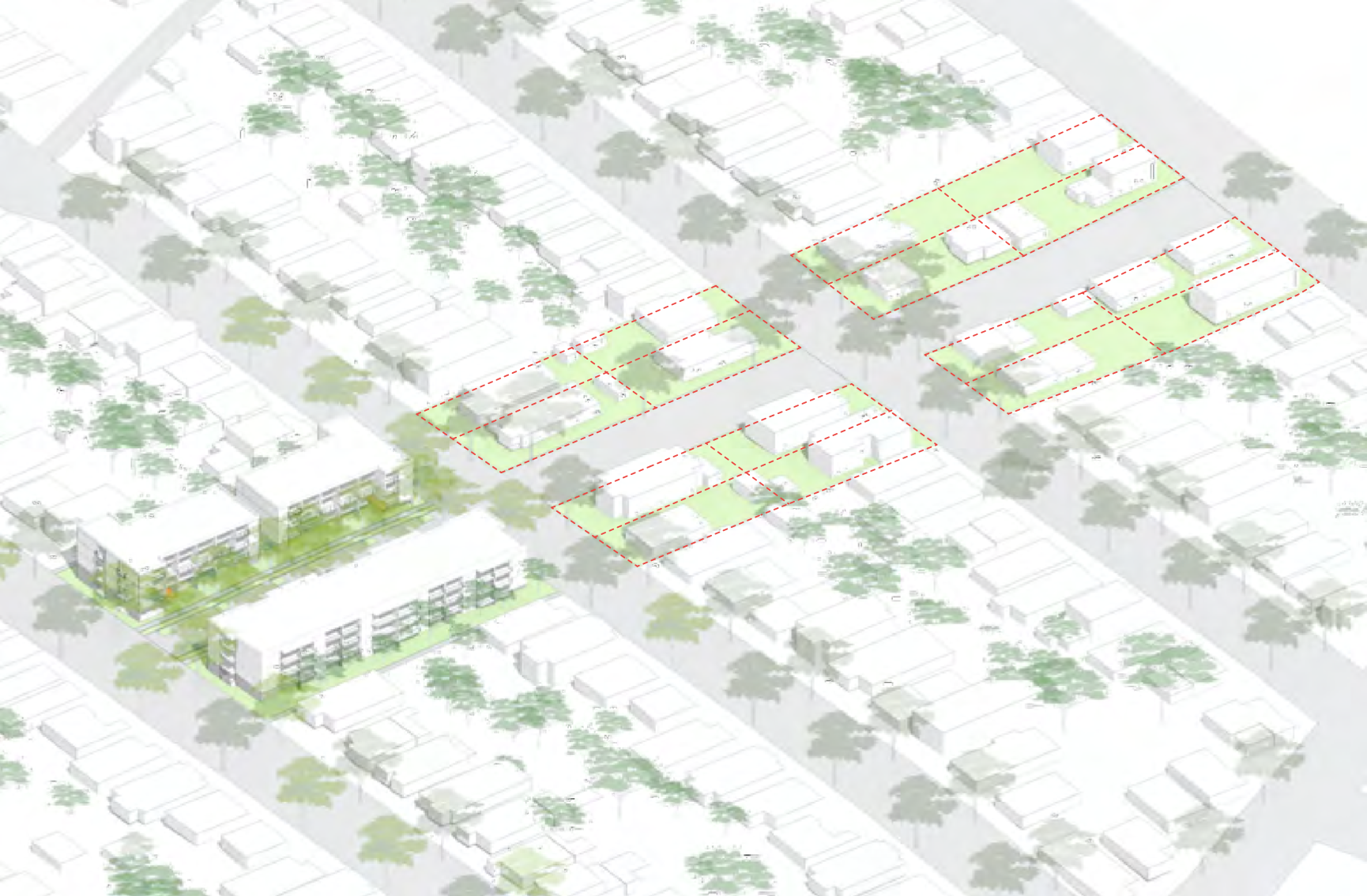

What was particularly interesting about the McGregor Westlake proposition following the extensive evaluation of the Ashfield context was that there were just 3 different project types that could be delivered across the study area that equated to just 5.5% of the existing residential lots but had the capacity to deliver a 31% increase (2,450 dwellings) without significantly changing the character of the existing 1900s suburb.Concurrently the projects improved streetscape character, better delineated park edges and passive surveillance, introduced mid block connections (where these could improve walkability) as well as delivering other important public improvement initiatives and metrics. These 3 project types are illustrated below:

Fig 2. Project types identified by McGregor Westlake for the ‘Missing Middle’ (source: McGregor Westlake for GANSW)

They can be summarised as follows:

Block End Projects sought to redress poor side fence conditions at the ends of urban blocks by permitting consolidations to create new street frontages.

Public Street Edges to Parks sought to create public interfaces and provide better passive surveillance of parks (to replace mute back fences).

New Through Street / Shared Ways sought to create new public thoroughfares in large blocks where new through site links were desirable for improved walkability.

In each case buildings of 3 – 4.5 storeys buildings were introduced, locally increasing density, while improving or repairing urban conditions and creating new streets with an understanding that public frontage translates to amenity (both public and private). The uplift facilitated development viability but importantly intervention was limited to just 5.5% of existing lots across the study area, thereby retaining the predominant character of existing neighbourhoods.

Furthermore, these project types are not particular to Ashfield. They are more broadly applicable across any Middle ring suburb (where lot sizes and conditions are comparable).

The application of these project types to the study area demonstrate that it is not only possible to make significant increases to density, via strategic interventions that substantially retain the preexisting residential stock and character of middle ring suburbs but to counter NIMBY activism by limiting impact to few sites. This contrasts the ‘Low Rise Housing Diversity Code’ which was perceived to have broad application and accordingly suffered from significant political scaremongering (even though the practical reality of the Code was limited due to technical and economic factors which severely curtailed its application).

Fig 3. A demonstration of project Type A – Block end Project, demonstrating how the predominant character of the suburb can be retained while converting a previously side fence frontage to a more public address with increased density. (source: McGregor Westlake for GANSW)

What is needed to achieve such a plan is for Councils and NSW Planning to recognise such project types (and potentially others) and to embed them into local LEPs and other planning instruments with an the understanding and associated confidence that the predominant character of neighbourhoods will remain largely intact but with increased capacity and potential to deliver housing diversity.

The significance of the ‘Missing Middle’ is that the city’s population can be consolidated over its existing footprint without the adverse impacts of expanding into pastures and forests, or building disruptive tower development, allowing the city’s preexisting infrastructure to be used more economically, efficiently and sustainably.

This is why the ‘Missing Middle’ is so important!