What’s Happened to Medium Density Housing?

A tale told in graphs of ABS dwelling approvals data.

An example of 1940's small form (4 pack) apartment buildings with on street parking

Anecdotally it seems delivery of housing in Sydney has been polarised; detached houses in suburbs at the periphery of metropolitan Sydney (sprawl) entrenched with inequitable access to public transport and opportunities for work, and at the polar opposite; high rise apartments within dense metropolitan centres with immediate proximity to railway stations, in urban contexts without the necessary preconditions for high density living.

But is this a fair assessment of what’s going on?

This got me curious, so I started mining ABS data to unpack whether the reality reflects the anecdotal evidence, and importantly to understand ‘Why?’.

Here I will pose a series of questions and allow the graphs, with abbreviated summaries, to do the talking. This work will inevitably develop into a more thorough investigation (currently in train) but for the purposes of this article I have prioritised brevity and a few key examples.

But before we start, it is important to understand ABS data and how it has been aggregated and represented here for our purposes. To that end, the following table has been provided to explain typological categories represented by different coloured bands within the graphs and associations with NCC (National Construction Code) Class types.

Question 1 - Has there been an erosion of Medium Density housing in NSW?

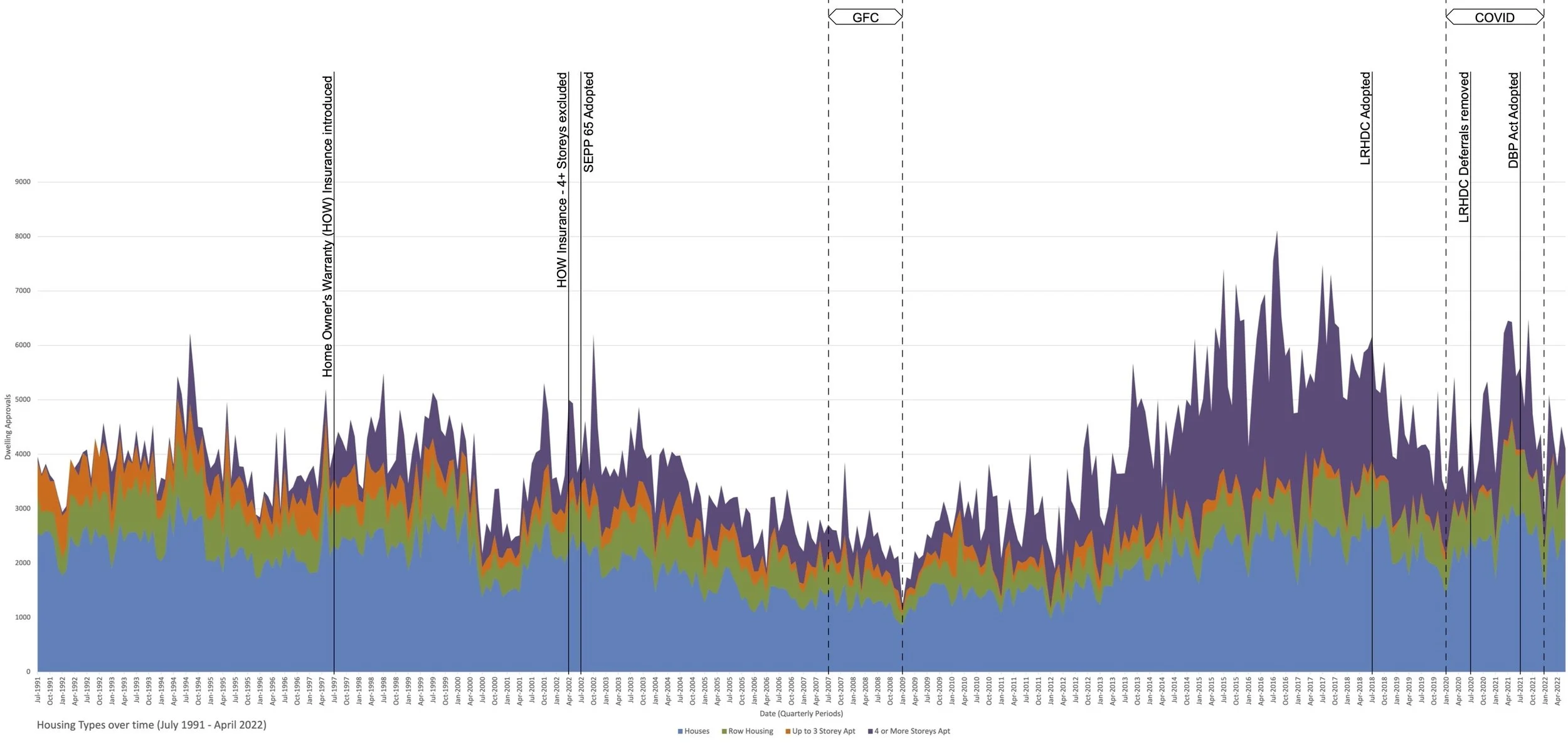

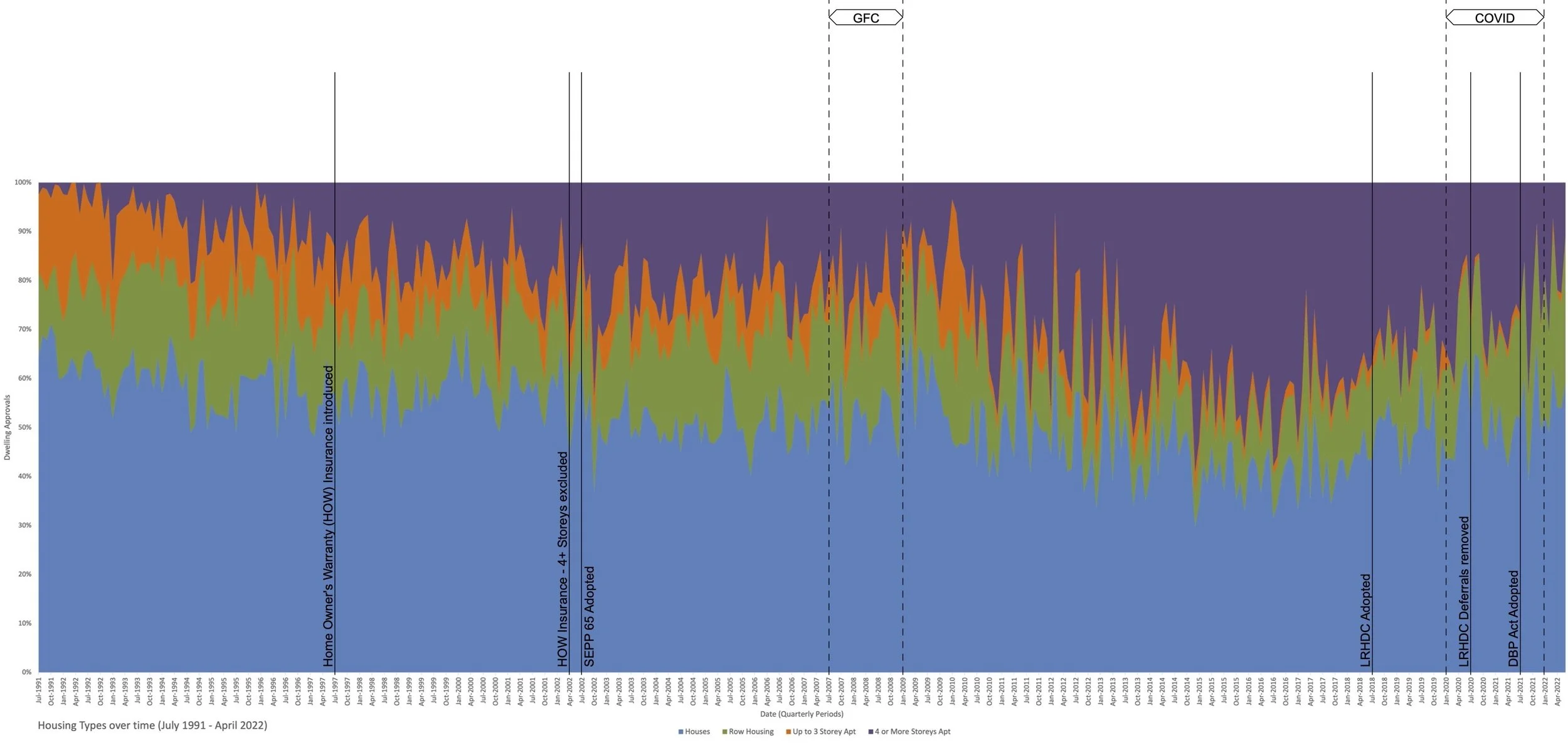

Examining ABS data of dwelling approvals, dating back to July 1991 (over 3 decades) it is clear that apartment buildings up to 3 storeys (orange band) have constituted a diminishing share of dwelling approvals in both number and proportion.

With a number of key policies relating to the delivery of housing overlaid we can perhaps start to identify whether these have had any bearing on dwelling approvals with some understanding or hypothesis with regard to their impact.

The following two graphs identify dwelling approvals (from July 1991 to April 2022) in total number of approvals (Fig 1) and by proportion of total approvals (Fig 2) respectively.

Fig 1. (above) Dwelling Approvals by type (July 1991 - April 2022) - total number of approvals per quarter (above)

Fig 2. (above) Dwelling Approvals by type (July 1991 - April 2022) - proportion of total approvals per quarter (above)

It is clear that there has been a diminishing volume and proportion of up to 3 storey apartment types; from about 18% of approvals in 1991 to less than 1% in 2022 and which corresponds with a dramatic decrease in 3 storey apartment approvals (by 95% - just 5% of 1991 levels).

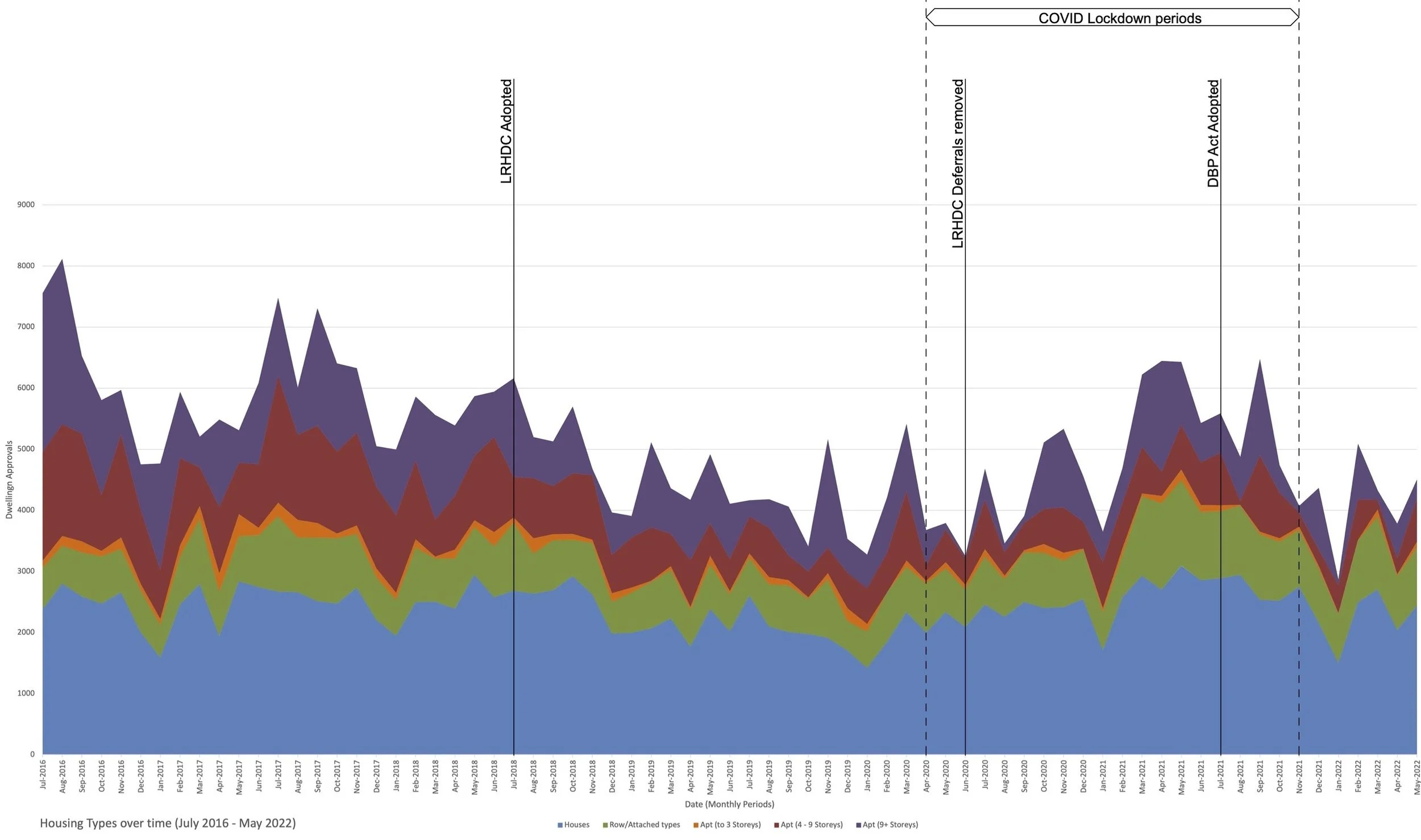

So, let’s have a look at the more recently available data set (from July 1996) that separates out the 4-9 storey category (red) from the 9+ storey category (purple) while posing the following question.

Question 2 - Has recent legislation had an impact on dwelling approvals for medium density housing?

Fig 3. (above) Dwelling Approvals by type (July 2016 - May 2022) total number of approvals per month (above).

Examining the more recently available ABS data that separates the 4-9 storey apartment buildings from 9+ storey apartment buildings (since July 2016) there is a correlation with impact resulting from two recent pieces of legislation relating to the delivery of medium density housing; notably the NSW Low Rise Housing Diversity (LRHD) Code and the DBP Act.

Low Rise Housing Diversity Code

Following the introduction of the LRHD Code in July 2018 there does not appear to be any significant shift or redistribution of preference towards different dwelling types. It is not until the lifting of the deferral period (affecting mostly metropolitan LGAs of Sydney) by July 2020 that we start to see an increase in row and attached housing types. This increase can be attributed to the benefit of an alternate approval pathway and the certainty offered by complying development for row and attached housing types permitted by the new Code.

There is little sign of any expansion in the ‘up to 3 storey apartment’ types which can be attributed to a greater uptake in Manor Houses permitted by the Code (which can be evidenced from other sources).

If anything it appears that preference may have been diverted from medium density apartment types (orange and red bands) to attached and row house types (green), and this is particularly noticeable following the introduction of the DBP Act, because the DBP Act placed onerous conditions on registration, process and submission requirements which disproportionately disadvantages small form apartment buildings (but not row housing).

I have written separately about how the Low Rise Housing Diversity Code failed to deliver housing diversity here which provides some further background with regard to the way the implementation of the Code affected small form apartment buildings (Manor houses) as well as attached types.

DBP Act

It is clear that there has been a gradual and historic decline of ‘up to 3 Storey’ apartment buildings, but most noticeable is the decline of this category immediately following the introduction of the DBP Act. Dwelling approvals in the period leading up to adoption of the DBP Act (up to July 2021) approximate 140 dwellings per month. Dwelling approvals following the introduction of the DBP Act diminish to typically less than 40 dwelling approvals per month ie. a reduction to almost a third immediately following the introduction of the Code.

I have written about the associated implications of the DBP Act more broadly here including the disproportionate liability and imposition it places on small NCC Class 2 development projects.

There is much to unpack from this work, particularly over the long term, and it is possible to further filter ABS data to tease out particular patterns relating to specific LGAs, regions (middle ring suburbs, metropolitan versus regional etc.) or specific policies.

From my own experience (confirmed by ABS data) it is clear that there have been a number of factors contributing to the demise of medium density apartments and these have been accumulating over decades to create a 'sour spot' in housing density - notably apartment buildings up to 3 (and 4) storeys.

I have summarised some of these factors here:

Policy Factors

LEP definitions have a limiting effect on low rise medium density housing types because any housing type with a common lobby, or that stacks apartments vertically is limited to a definition of a ‘Residential Flat Building’ including categorisation as NCC Class 2 which triggers the requirements of the DBP Act;

The only exception to the above are Manor Houses which can be built in areas designated for ‘Multi Dwelling Housing’, but are still categorised as Class 2.

Zoning maps limit 'Residential Flat Buildings' to R3 medium density and R4 High density zones but not the broader R2 zones where medium density housing types have historically existed.

The removal of the requirement (in April 2002) for Home owners Warranty (HOW) Insurance (previously all inclusive) to insure apartment buildings containing 3 or more storeys was removed and economically disadvantages buildings with less than 3 storeys of apartments, shifting the delivery to attached and 4+ storey apartment buildings where possible.

SEPP 65 which applies to buildings that are three or more storeys and contain more than 4 dwellings places increased restriction on building separation etc. which can dimensionally limit the provision of 3 storey apartments as infill projects.

The NCC more recently introduced requirements for sprinklers in buildings containing 4 or more storeys of apartments (previously required for 9+ storeys). This has economically disadvantaging apartment buildings with as little as four storeys with additional services requirements and maintenance.

The DBP Act which is applicable to all NCC Class 2 buildings (including only 2 dwellings vertically separated [as a duplex] or row housing over a common carpark) is a significant deterrent to small scale apartment buildings, as it places onerous requirements on process, registration, submission requirement, risk and associated fees which disproportionately disadvantage smaller apartment developments (but not attached housing types which can be categorised as Class 1).

Integrating the (usually mandated minimum) carparking requirements by Local Development Control Plans into small form infill development is not only dimensionally and constructionally challenging due to the scale of development but expensive.

Economic + Other Factors

Feasibilities for small form residential development projects need to account for Strata title types (townhouses and apartments) that are valued at a fraction of Torrens title (free standing houses) types which affects feasibility relative to attached (Torrens title) types eg. duplexes or 'semis'. Accordingly, a replacement rate of 9+ apartments per single free standing dwelling* is generally required for feasible redevelopment. This has effectively limited the viability of Manor Houses (which limit apartments to 4 apartments by definition) and other such small form apartment buildings

The policies of lending institutions penalise 3 or more dwellings (for small form apartment buildings) with onerous commercial rates, which compound the problems for economically feasible development.

If we return to the original graph (Fig 1) we can start to understand that there are compounding factors over several decades that have had an impact on the delivery of medium density housing and that these have most disproportionately impacted apartment buildings up to 3 (and 4) storeys to create a 'sour spot' in housing density. This article is neither conclusive nor complete, but rather a demonstration of key factors that are acting as undercurrents to the delivery of medium density housing.

We simply don't have a suitable policy framework for viable medium density housing. Unless we garner the will to develop some positive policy initiatives that redress this 'sour spot' we won't be able to develop suitable models for infill that may serve to replace free standing dwellings within our middle ring suburbs, nor will we be able to address our perpetual horizontal and vertical sprawl.

*Updated in 2024.